The country continues to face a heritage crisis of monumental proportions despite several government initiatives over the decades. Can public–private partnerships, leveraging adaptive reuse, help revive its built legacy?

New Delhi:

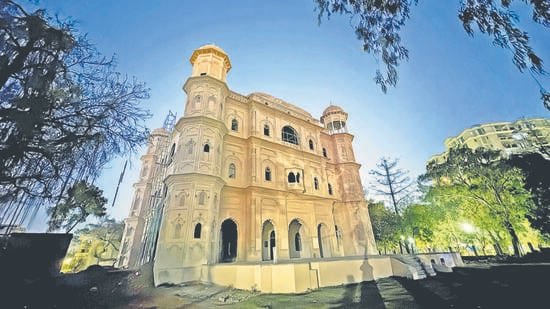

In the heart of Lucknow, the majestic Chhatar Manzil stands as a silent witness to the city’s Nawabi past. Its umbrella-shaped dome and Indo-European architecture once symbolised opulence and cultural fusion. Today, parts of this 19th-century icon are crumbling after years of neglect. But its fortunes may soon change. Earlier this year, the Uttar Pradesh government announced plans to de-notify and lease several state-protected historic buildings, including Chhatar Manzil, to private firms for 30–90 years under public–private partnerships (PPPs), aiming to transform them into cultural hubs, museums, hotels, and tourism hotspots through adaptive reuse.

Last month, chief minister Yogi Adityanath urged the Centre to transfer four forts currently protected by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI)—Talbehat Fort (Lalitpur), Kalinjar Fort (Banda), Madfa (Chitrakoot), and the Barua Sagar Ghats steps (Jhansi)—to the state for tourism-focused development.

Beyond such high-profile efforts, countless other sites remain forgotten. Across India, towns and cities are dotted with crumbling palaces, havelis, and monuments—from Rajasthan’s fortresses and Delhi’s Mughal relics to Kolkata’s colonial mansions and Tamil Nadu’s coastal temples. Despite numerous central and state initiatives, much of this heritage languishes in neglect.

The scale of India’s heritage crisis is immense. A 2021 Niti Aayog study by the Dronah Foundation, a non-profit focused on heritage research and conservation, estimates that India has over 500,000 heritage structures and sites. Yet only about 100,000 are officially listed, and a mere 7% enjoy legal protection. The Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains (AMASR) Act, 2010, along with various state archaeology laws, safeguards around 8,000 structures—approximately 3,700 under the ASI and 4,377 under state archaeology departments. Municipalities in about 60 cities maintain another 30,000 heritage structures through local urban heritage cells.

The ASI itself is under strain. As of March 2025, about 45% of posts in the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) were vacant, with only 4,845 employees against a sanctioned strength of 8,755, Union Culture Minister Gajendra Singh Shekhawat informed Parliament on March 10. Its budget for 2025–26 is ₹1,278.49 crore—a marginal rise from ₹1,273.91 crore the year before—widely seen as inadequate for an organisation tasked with protecting and excavating India’s vast archaeological heritage. “Considering the increasing pressure on ASI’s existing resources, the allocation needs to be increased to ensure timely conservation and meet global standards for preservation,” a parliamentary panel noted in March.

“One of the greatest challenges is effectively recording, documenting, protecting, and interpreting the vast array of heritage across India,” says Shikha Jain, conservation architect and founding director of Dronah Foundation, which is currently hosting The Historic Cities Series 2025 with the National Institute of Urban Affairs (NIUA). Since April, over 20 cities have held dialogues on heritage planning, toolkits, and interpretation, highlighting multidisciplinary approaches to sustain heritage amid urban change.

A patchwork approach to conservation

India’s approach to conserving built heritage has long been a patchwork of schemes and missions that together attempt to address a complex challenge. The HRIDAY (Heritage City Development and Augmentation Yojana), launched in 2015 by the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs, aimed to integrate heritage-sensitive planning in 12 historic cities, including Varanasi, Amritsar, Ajmer, and Puri. Fully funded by the Centre, HRIDAY sought to combine infrastructure upgrades with heritage restoration, but coordination gaps and weak local capacity resulted in uneven outcomes.

Similarly, the Adopt a Heritage: Apni Dharohar, Apni Pehchaan scheme, launched in 2017 and revamped as Adopt a Heritage 2.0 in 2023, allows private firms and PSUs—called Monument Mitras—to maintain and enhance visitor amenities at selected monuments through CSR funding, under ASI supervision. The Smart Cities Mission also supported conservation-linked renewal through adaptive reuse of old buildings, waterfront revival, and façade improvement projects in heritage-rich cities such as Gwalior, Jaipur, Udaipur, and Varanasi.

Other efforts include the National Mission on Monuments and Antiquities (NMMA, 2007), which documents heritage across India, and the National Culture Fund (1996), which channels private and philanthropic donations into conservation.

But the absence of a coherent national policy, fragmented institutional responsibilities, and weak local capacity continue to limit their impact. “What we need is a robust conservation policy with clear guidelines, structured investment through PPPs, and stronger community involvement,” says Aishwarya Tipnis, a Delhi-based conservation architect. “The focus must go beyond monuments to include everyday heritage. Conservation should be democratized—participatory and accessible to all.”

The Niti Aayog study also highlights another challenge: heritage structures are scattered across multiple custodians—the ministries of culture, railways, ports, shipping, and waterways. For instance, the Directorate General of Lighthouses and Lightships manages historic coastal lighthouses, yet this maritime heritage largely falls outside formal conservation frameworks. Most departments, the study notes, are ill-equipped to safeguard their heritage, underscoring the need for greater awareness, inter-agency coordination, and capacity building.

Partnering for preservation: Can PPPs truly help?

Many see PPPs as key to bridging gaps in heritage conservation by mobilising private expertise, funding, and technology. The restoration of Sunder Nursery in Delhi—a collaboration between the Aga Khan Trust for Culture, ASI, CPWD, and the South Delhi Municipal Corporation—is often cited as a model of how such partnerships can transform neglected sites into vibrant public spaces.

“India’s heritage is vast, and public funds alone cannot meet the demand,” says Dikshu Kukreja, architect and urbanist. “PPPs can bring investment, expertise, and year-round programming, but private partners need operational freedom within clear guidelines, and the ASI must ensure conservation standards.” He adds that Sunder Nursery project shows that when conservation and public benefit come first, PPPs can create world-class cultural landscapes and boost tourism.

“When government funding is limited, bureaucratic norms often restrict hiring skilled craftsmen or specialists, and choosing the lowest bidder may compromise results,” says Vikas Dilawari, a Mumbai-based conservation architect. “PPPs offer greater flexibility to assemble the right experts, manage costs, and adapt to site challenges. They allow uncertainties—like hidden damage—to be addressed through sample works, careful agency selection, and monitoring.”

But many warn that PPP projects risk turning heritage into exclusive commercial assets, such as hotels inaccessible to the public. “The success of a PPP hinges on a monument’s historical value, scale, and condition. The most impactful projects I’ve worked on, often funded through CSR, prioritise cultural integrity over commercialisation,” says Dilawari, who restored the CSMVS Museum with support from the TCS Foundation and the Dr. Bhau Daji Lad Museum in collaboration with the Jamnalal Bajaj Foundation, BMC, and INTACH.

Private support remains sparse

Private participation in heritage conservation remains limited—mostly small-scale and CSR-driven. According to a reply by the Minister of Culture in the Rajya Sabha in February, the National Culture Fund (NCF) received ₹17.51 crore in CSR funding between 2021 and 2024 for conservation and maintenance of monuments. Contributions came from Infosys Foundation, Sony India, Airports Authority of India, Bhilai Steel Plant, and others, supporting projects such as the Vishnu Temple at Bateshwar (Madhya Pradesh), ASI Hampi Museum upgrades, and restoration at Deobaloda (Chhattisgarh). No CSR funds were received through NCF for any project in Uttar Pradesh or Bihar.

Similarly, the “Adopt a Heritage” programme, launched by the tourism ministry in 2017, saw limited success with only 10 of 93 monuments adopted. Its revamped version under the culture ministry in 2023 also struggles, with just 28 monuments adopted so far. “Most companies show interest only in larger, high-profile monuments. The ASI continues to maintain all monuments under its purview within available staff and funds,” says Nandini Bhattacharya Sahu, Joint Director General, ASI. “PPPs are welcome, but public participation— in the form of better behaviour and respect for heritage—is equally important.”

A July 2025 KPMG report, Building Public-Private Synergies for Heritage Conservation, in partnership with the PHD Chamber of Commerce and Industry (PHDCCI), outlines how public-private models can advance heritage conservation in India. It calls for treating heritage as a developmental priority linked to community inclusion, resilience, and economic growth. The report highlights adaptive reuse, digital preservation, and AR/VR to enhance visitor experiences, while noting challenges such as funding gaps, limited expertise, and weak community engagement. It urges inclusive policies, fiscal incentives, and stronger PPPs to promote sustainable, tourism-led development.

Many believe the UK’s National Trust model offers lessons. “It provides professional stewardship with ring-fenced maintenance funds and strict design review. India can adapt this by setting up independent heritage trusts in major cities with community representatives,” says Kukreja.

Founded in 1895, the UK National Trust preserves historic buildings, gardens, and landscapes through a membership-based model that funds maintenance and restoration. Properties are managed under strict covenants, with income reinvested in upkeep and public engagement encouraged through events and volunteer programmes. It also receives major backing from the National Lottery Heritage Fund, which since 1994 has granted over £9.5 billion to more than 53,000 heritage projects.

“India has enough frameworks for PPPs and community participation, the problem is while people express pride in heritage, few invest in it. Even INTACH struggles to mobilize private funds,” says A.G.K. Menon, urban planner and conservation architect.

Adaptive alchemy: heritage reborn

There is hope, however, in examples of adaptive reuse that blend preservation with new purpose. In cities like Lucknow, Kolkata, and Puducherry, neglected heritage structures are being transformed into cultural venues, cafés, and public spaces—showing that heritage can be relevant and economically sustainable.

Puducherry offers a strong case. Through collaboration between Puducherry Smart City Development Limited, the Department of Art and Culture, and INTACH, the Union Territory has invested over ₹100 crore since 2020 to revive the French and Tamil Quarters. Colonial-era churches, bungalows, and public buildings—including Calve College—have been restored using traditional materials and techniques. Residents and shopkeepers joined in by repainting façades of their building in heritage colours and participating in awareness drives, demonstrating how collective efforts can sustain heritage.

In Kolkata, dilapidated colonial bungalows are being revitalised into cafés and boutique hotels. Bhawanipur House (1907), a restored bungalow turned multi-level café, blends classic architecture with modern interiors. Similarly, Calcutta Bungalow, a restored 1920s townhouse, has been converted into a heritage hotel that honours the city’s history through themed rooms and preserved details.

“Kolkata has thousands of heritage buildings with complex ownership patterns, and a one-size-fits-all model cannot work. PPPs and community-led collaborations can complement each other,” says Mukul Agarwal, founder-trustee of the Kolkata Heritage Collective, founder-trustee of the Kolkata Heritage Collective, a citizen-led trust, dedicated to restoring and reusing Kolkata’s built heritage. “Smaller initiatives may offer realistic solutions for densely inhabited neighbourhoods, where heritage-sensitive maintenance or awareness campaigns can be more effective. Such projects nurture local ownership and preserve cultural memory.”

She adds: “Large, high-visibility sites such as colonial-era public buildings or grand mansions can benefit from PPPs that allow adaptive reuse—turning them into museums, boutique hotels, or cultural hubs.”

Her observation finds echo in the city’s recent effort to revive forgotten landmarks. In July, the Kolkata Municipal Corporation (KMC) signed an MoU with CREDAI Kolkata to restore Roxy Cinema, an Art Deco opera house-turned-movie theatre at Esplanade. “The exterior restoration was completed by KMC, and we’re investing ₹5 crore in the interiors to create an auditorium and event space,” says Apurva Salarpuria, president, CREDAI Kolkata.

“Adaptive reuse is a viable solution for heritage conservation, but challenges such as multiple ownership of buildings and shortage of skilled labour and contractors experienced in conservation techniques remain,” says Jain.

Back in Lucknow, the 110-year-old Butler Palace—built in 1915 for Sir Spencer Harcourt Butler—is being restored by the Lucknow Development Authority (LDA) into a cultural hub at a cost of ₹3.78 crore. Scheduled for completion by early next year, the project includes structural repairs and heritage-sensitive interiors. “Exterior and structural work are largely complete, while interior refurbishments are underway,” says an LDA official.

Kukreja emphasises that preservation alone isn’t enough. “Heritage structures do not exist in isolation. The surrounding urban environment—roads, public transport, last-mile connectivity and urban design—also needs careful planning,” he says, adding that only coordinated efforts can preserve India’s vast legacy and ensure it remains relevant for future generations.